Finished is Better than Perfect

How to not let the great get in the way of the good

Consider this a small rant about decision paralysis.

Some choices are small and easily forgotten. Others end up defining careers, relationships, or entire chapters of our lives. What often matters more than the choice itself is how long we spend circling it. The pressure to get it exactly right can make even simple decisions feel high-stakes. A big part of it, I think, comes from the very human tendency to want to wait for something better. A better plan, a better moment, a better signal. It’s easy to think that holding out for the “great” outcome is the smart move. But that’s often where progress breaks down.

Good decision-making doesn’t always come from more logic or more instinct. It comes from movement, or testing, or experimenting. In most cases, the options are workable. The real challenge is how long we hesitate. We treat complexity like a sign of depth and more information like a guarantee of better outcomes. So what ends up happening is that we ask more questions, tweak the model again, and try to get one step closer to certainty. The work starts to look thoughtful on the surface, but underneath it’s something else entirely. We’re waiting for something that may never come (or worse, we’re stalling while we make our analysis look pretty and sophisticated).

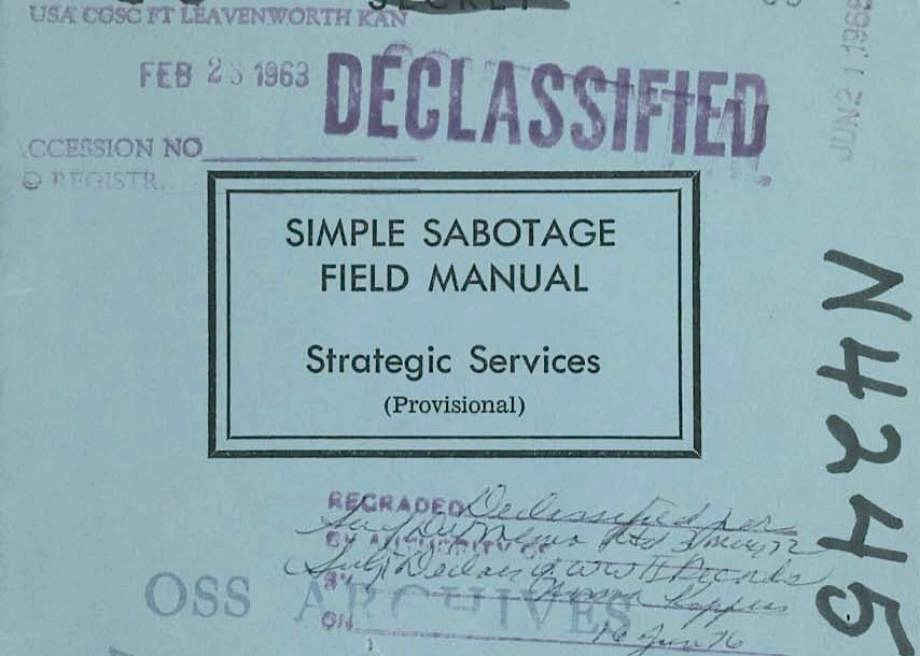

You’ve seen it play out in strategy sessions and planning meetings. A decision is close, but not quite ready. Someone suggests waiting until the next check-in call. The model gets revised again. Everyone agrees to revisit later. The delay feels harmless. The logic feels sound. But nothing moves. The same thing happens in hiring, in product roadmaps, in investments. The bar keeps rising. And eventually, momentum fades. Which, incidentally, is a core part of the CIA’s recommend steps on how to resist authoritarian rule.

Excerpt from the CIA’s Simple Sabotage Field Manual: To lower morale and production, think of the worst boss you’ve had and act like that. Be pleasant to inefficient workers; give them undeserved promotions. Discriminate against efficient workers; complain unjustly about their work. When possible, refer all matters to committees for "further study and consideration." Attempt to make the committees as large and bureaucratic as possible.

Now, there’s a difference between refining and avoiding. It helps to know when your decision process is no longer adding value. If you’re circling the same inputs, hoping for a breakthrough, you may have already passed the moment where action would have mattered most. There’s no perfect time. Conditions are rarely complete. The most effective among us move with what we have and stay ready to adapt.

Waiting for “great” can feel like the responsible thing to do. But in reality, it’s often a risk of its own. Good decisions, made with focus and intention, often beat perfect decisions that never happen. Progress tends to reward people who choose a direction and commit to it. You can always revise or shift. What you can’t do is make any real change while standing still.

And so, at a certain point, the right move is the one that gets you going. The hesitation is understandable. But in the end, the path doesn’t have to be perfect. It just has to be chosen.